Report from Yazd

Ed Crocker

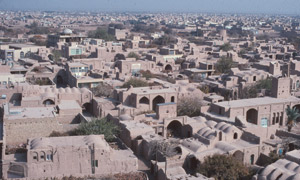

Last month at this time the 9th International Conference on the Study and Conservation of Earthen Architecture was convened in Yazd, Iran. The gathering was exceptional not only for the wealth of information about mud buildings that was concentrated in one spot, but because of the place itself.

Yazd is located at the edge of the Dasht-e-kavir desert, which competes with the Atacama as the driest place on Earth. The beauty and comfort inherent in the response of the builders of the city to the harsh environment is breathtaking: adobe wind towers catch the desert breezes and cool the air as it descends into the living spaces; water is transported for miles beneath the desert from mountain sources in a complex series of ancient underground aqueducts called qanats; homes are built around open courtyards with gardens and pools, seemingly extravagant in a region that gets less than a half-inch of rain per year; and there is no concession made to the austere as homes, palaces and mosques alike are highly decorated, pleasant and comfortable.

Yazd is located at the edge of the Dasht-e-kavir desert, which competes with the Atacama as the driest place on Earth. The beauty and comfort inherent in the response of the builders of the city to the harsh environment is breathtaking: adobe wind towers catch the desert breezes and cool the air as it descends into the living spaces; water is transported for miles beneath the desert from mountain sources in a complex series of ancient underground aqueducts called qanats; homes are built around open courtyards with gardens and pools, seemingly extravagant in a region that gets less than a half-inch of rain per year; and there is no concession made to the austere as homes, palaces and mosques alike are highly decorated, pleasant and comfortable.

The conference itself was held in the Dowlat Abad Garden (AD 1747), a complex of spacious earthen buildings amid some 40 acres of formal gardens with marvelous reflecting pools, pomegranate orchards, rose beds and pathways. The speaking hall was the spacious old stable whose beautifully plastered interior earth walls are lined with individual feeding troughs where, it would seem, the horses who arrived at this little paradise were treated as luxuriously as their riders.

Perhaps most remarkable of all is that, in large part, the garden was restored over the course of the last two years when the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization's offer to host the conference was accepted. This was just one sign of the enthusiasm and commitment to the project, and a high indicator of how much importance the Iranians place on hospitality. Each attendee was met at the airport with a rose, a packet of information and a taxi ready to deliver us to our accommodations. Most of us were unsure how freely we could move around on our own, a fear that turned out to be completely unfounded. A friend from Santa Fe, Francisco Uviña, and I rented a car and driver for two days and despite the formidable language barrier, traveled far and wide to earthen sites and a Zoroastrian shrine in the desert. We never, not once, felt uncomfortable, unsafe or unwelcome. I have to say that of the forty-odd countries that I have visited, Iran is unequivocally the most hospitable.

The papers presented at the conference were exceptional as well. There were, of course, some that were as dry as dust, including two in a row that used PowerPoint in its worst form to illustrate the comparative moisture-absorbtion/expansion-rates of Montmorillonite v. Kaolinite. Interesting to some, and important I am sure in certain circles -- but soporific when the chairs were as comfortable as those in our stable were. Among the highlights were some astonishing reports on protection of sites in Central Asia, including saving what is left of the Bamiyan Buddha in Afghanistan that was blown up by the Taliban a few years back; the first paper I have ever heard on earthen ramparts in Russia; and a marvelous presentation on the Japanese contributions (both financial and scientific) to the conservation of earthen sites in East Asia. Without exaggeration or embellishment, among the top three most interesting and well-received contributions was Francisco's paper on the amazing work still ongoing with Cornerstones in collaboration with the Mexicans.

So there you have it -- or a small part at least. What I haven't covered are the ancient earthen caravanserai (this is, after all, Persia on the Silk Road), the Zoroastrian towers of silence where bodies were left for consumption by vultures until just thirty years ago, and Isfahan. That is another world that not one of us should feel afraid to visit.