Foundation Repairs in Historic Earthen Buildings

Ed Crocker

Movement in walls and footings is one of the most challenging problems faced in restoration projects. Masonry walls moving either vertically or as a consequence of soil settlement can be dangerous to live near and equally perilous to repair.

Many of the earthen buildings in the southwestern United States were built on shallow foundations, or on no foundation at all. Most are fine, having "settled in" to their sites and done all the cracking they will likely ever do within a few years after construction. Some, however, have been subjected to excessive amounts of moisture through capillarity, flooding, hard platering or changes in ground water levels. In some cases the only conservation remedy is to retrofit the building with a footing. Following are three proven methods for doing that, including one "high-tech" adaptation to low-tech failures.

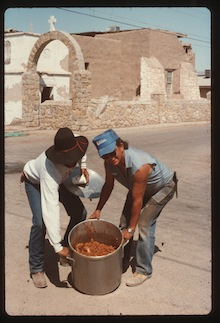

When Cornerstones Community Partnerships began the stabilization of the Doña Ana church in southern New Mexico, the first thing we did was to shore the entire building. Good thing. When we proceeded to the second task, the rebuilding of the wall bases, the entire east wall of the nave collapsed. Only moderately perturbed and having suffered no injuries, we proceeded with the rebuilding of the entire wall.

The original wall in Doña Ana didn't have a bad footing, it had no footing at all. The first course of adobes had been laid directly on the ground. Finding ourselves at ground level after cleanup, we chose to install a cobble and gravel footing. Since the frost line in Doña Ana is only 6 inches, a shallow trench was dug to a width of 36 inches and a depth of twelve inches. River cobbles were evenly spread over the floor of the trench, and then covered with round gravel to the original ground surface. The first mortar joint was laid directly on top of the gravel with no moisture barrier between. The gravel bed with its network of interstitial air spaces is an effective capillarity break for ground water as well as a conduit to the permeable soils below for any water entering from above.

Another precarious situation existed in the wall bases of a historic farmhouse (ca. 1850) in the Hondo Valley, west of Roswell, New Mexico. There the wall bases were so eroded by moisture retention and flood irrigation that I could practically crawl through some of the holes. The owner, admirably desiring to save the fabric of the old building, was willing to go to great lengths to salvage what remained of the structure.

We proposed, and built, ledgestone footings under the devastated adobe walls. For a change we didn't provoke a collapse. The building was shored vertically from within, and additional temporary lateral, buttress-style supports were installed against the exterior walls. Alternating four-foot sections of the wall were undermined and a shallow trench dug. The adobe wall was then repaired and the ledgestone footing laid up in mud to connect with the wall safely above grade. The job was finished with the installation of a redundant drainage system around the periphery.

If pebbles, mud and ledgestone don't appeal, galvanized steel helices and girders are the basis for another approach. For over seventy years, helical piers have been proven an effective and moderately priced solution to stabilizing both new and older buildings on unstable soils. The principle is simple; soil testing provides a profile of the subsurface, including moisture content, voids, and grannulometry. By calculating the load to be supported and configuring the intervention to the soil profiles, a system of helical piers can be installed to support practically any load. The piers, reminiscent of an auger, but with single helixes instead of a continuous spiral, are hydraulically screwed into the ground at calculated intervals. The tops of the piers are then attached by any number of clever devices to the base of the walls. Once attached, the walls can be moved up or down to straighten out openings and correct for settlement.

We have used helical piers to retrofit virtually every category of structure, with existing foundations or without. By joining the tops of a series of piers together by means of cast concrete beams, steel baskets or girders, walls can very effectively be stabilized.

It's a topsy-turvy world when the last component of the building to be installed is the foundation; such are the vagaries of historic preservation.